Kayla’s Act Gives Hope for Victims of Domestic Violence

In the week of Thanksgiving 2022, Kayla Hammonds was brutally stabbed to death by her ex-boyfriend in a grocery store parking lot in Lumberton, NC. The ex-boyfriend, Desmond Sampson, had a significant prior history of violence, with Hammonds having filed multiple protective orders against him, including one two weeks prior to her death. However, on several occasions and just three days before her murder, Hammonds failed to appear in court to testify against Sampson because of violent threats he made against her, ultimately allowing his criminal charges to be dropped. This cycle of fear and intimidation marked Hammonds’ several years with Sampson, representing a familiar pattern that victims of domestic violence face and further highlighting the barriers these individuals experience in their efforts to seek help.

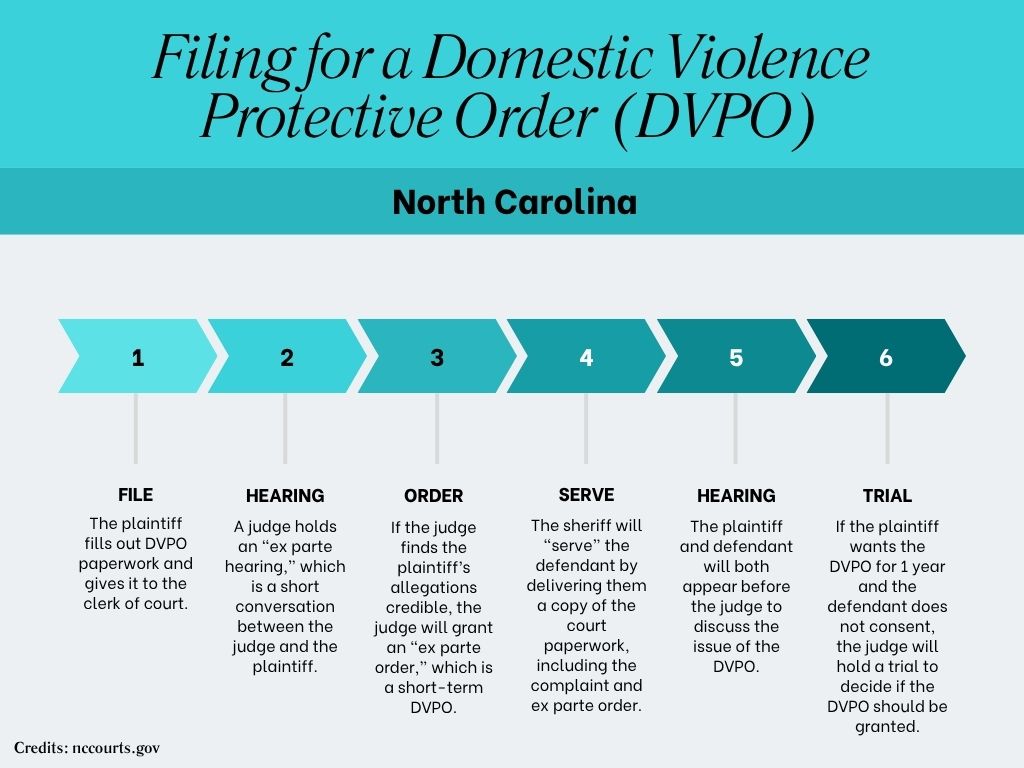

As a victim of domestic violence, Kayla Hammonds turned to a domestic violence protective order (DVPO) for hope, but it could not protect her from a person who was unconcerned with the law. When interviewed for the murder of Kayla Hammonds, Sheriff Burnis Wilkins stated, “Sadly, a DVPO is just a piece of paper, and evil will do evil things regardless of our actions.” When victims of domestic violence have the courage to reach out for help, they are holding onto hope that their situation will change. If DVPOs are going to be ineffective for some people, there needs to be an avenue for victims’ voices to be heard and taken seriously.

There have been a multitude of studies on the effectiveness of obtaining a domestic violence protective order (DVPO). One study found that women were 80% less likely to experience physical abuse in the year following the incident of abuse when they obtained a permanent protective order. In several studies, “women with permanent restraining orders were also at significantly less risk of physical abuse, fewer odds of contact, and fewer odds of sustained psychological abuse by the perpetrator compared to women who reported intimate partner violence but did not obtain restraining orders.”

In Kentucky, research was performed in five jurisdictions on the perspectives of civil protective orders, reporting that half of the women who obtained a protective order did not experience a violation of that order within the following six months. The other half who did experience violations revealed that the levels of violence and abuse declined significantly compared with the six months prior to obtaining the protective order. Generally speaking, DVPOs tend to be effective for a large percentage of individuals who obtain them; however, there are still some people whose problems do not go away with a DVPO.

Research investigating the factors that influence domestic violence restraining orders in Los Angeles, CA, noted that “while restraining orders are effective in about 69% of cases in terms of helping victims to separate from their abusers and stopping the abuse, there’s that other 31% of cases in which they do nothing.” In a survey on DomesticShelters.org, participants were asked what had occurred after they obtained an order of protection. “Over half the respondents said the protection order was violated, they reported it and nothing happened to the abuser. Only 16 percent said the protection order reduced or stopped unwanted contact.” Ensuring that all victims of domestic violence are able to obtain help when they finally muster the courage to ask is crucial for our justice system to uphold.

One issue with DVPOs is that they are seemingly ineffective when the abuser is determined to have their way. In a dissertation written by Thomas Tharpe, who studied at Walden University, research was conducted on female victims’ perceived effectiveness of civil protection orders in Tennessee. During an interview with one of the participants of the study, a woman explained the issue with DVPOs’ effectiveness when the abuser is not concerned with the law. “The weakness [of the civil protection order is] it’s just a piece of paper. If he had been more adamant about hurting me, he could have done that, and that piece of paper wouldn’t have done anything but been used as evidence against him in my murder trial, basically.” This sentiment rings true for victims like Kayla Hammonds when their abusers have little to no regard for the law and its consequences.

Another issue with the effectiveness of DVPOs is the perceived concern that law enforcement lacks the urgency to enforce the law, causing further concern for abusers who already have a disregard for the repercussions of their actions. When asked for an opinion on the enforcement of protection orders, one victim stated, “No one enforces it. Police won’t even do anything if you show them the paper. They say [the abuser] has to physically hit you again before [police] will enforce it and…they will just deny it unless you have ten witnesses and a whole recording when it happened for them to even arrest. It means nothing.” In one of Hammonds’ calls to police, law enforcement did not even dispatch to her location but simply told her to take out a DVPO. Having to plead with law enforcement to uphold their end of justice is not a reality that domestic violence victims should have to live with.

Victims of domestic violence face real danger when their abusers threaten them and their loved ones. When both abusers and law enforcement do not take the law seriously, it creates a system where victims are too afraid to testify and feel it is worthless and even dangerous for them to appear in court. In one study, “a family court in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reported that over one-third of protective order cases are dismissed because the survivor fails to appear often due to fear, intimidation, and access issues.”

In the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, courtrooms across the country had to quickly shift to remote hearings to accommodate the situation at hand. It is worth noting that “[V]ictim participation at restraining order hearings has swelled with the use of online hearings, as remote appearances can remove the specter of threats and intimidation from the abuser in open court, as well as other obstacles victims face.” However, over the last five years, most courts have switched back almost entirely to in-person proceedings. This is where trauma-informed practices become an important asset in domestic violence courts. By allowing each victim the right to choose remote testimony, the justice system is protecting victims from the effects of lethal threats and lessening an otherwise severely traumatic experience.

Kayla Hammonds’ life was not a unique situation. There are individuals every year who experience similar circumstances to those Hammonds faced from her relationship with a violent person, but for others, there is hope because of Kayla Hammonds. Because of the brutal manner of her death, Hammonds’ family and the community cried out for the justice system to do better for victims of domestic violence.

Kayla Hammonds’ grandfather, J.W. Hammonds, sought out what could be done to help ensure Kayla’s story was never repeated, and from that pursuit, House Bill 39 and Senate Bill 51 were born. Ultimately named “Kayla’s Act: Protecting Domestic Violence Victims,” House Bill 39 and Senate Bill 51 have created a more trauma-informed judicial system in North Carolina by removing common barriers that domestic violence victims encounter when attempting to seek help.

Kayla’s Act allows for victims of domestic violence to testify remotely, so they don’t have to face their abusers directly in court, which is a fear-ridden experience for most victims. It extends the statute of limitations from two years to ten years, allowing time to pass for victims who are too afraid in the moment to seek help and for old cases to resurface if they are unresolved. The Act also preserves and allows previous testimony to be used in cases to recognize patterns of abuse and criminal activity, especially for cases where abusers have seemingly scared victims out of testifying. This Act will give victims hope for change when they have sought help from their abusers through every other means, including DVPOs, and are still faced with threats and violence.

It then begs the question: if the laws in Kayla’s Act were available to Kayla Hammonds before her death, would she still be alive today?

Because of Kayla Hammonds, North Carolina is able to better serve its people by way of a more trauma-informed justice system. With Kayla’s Act allowing remote testimony for victims of domestic violence, there is hope that victims will be heard and their abusers will no longer walk free because of their successful efforts at intimidation. It is hard to reach out for help when you are a victim of domestic violence, and it should be the justice system’s responsibility to alleviate the barriers victims face to achieving justice for themselves. If not through a protective order, then through other means necessary for victims to feel safe.

With a bachelor’s degree in psychology, I have a special interest in issues pertaining to psychology and criminal justice. My desire is to eventually apply for graduate school for a degree in criminal justice. I currently work as a legal assistant, and I have the cutest dog named Bug.

Katie Sims