Education for Inmates Has Major Cost-Saving Benefits for Society

Before imprisonment, Martin spent most of his time working for a small, marginal family-run grocery store. The need to do his part in supporting the family unit prevented him from going to high school. At the age of 19, Martin was barely literate and in prison for a robbery, but yearning to improve himself. This is where prisoner education comes into play.

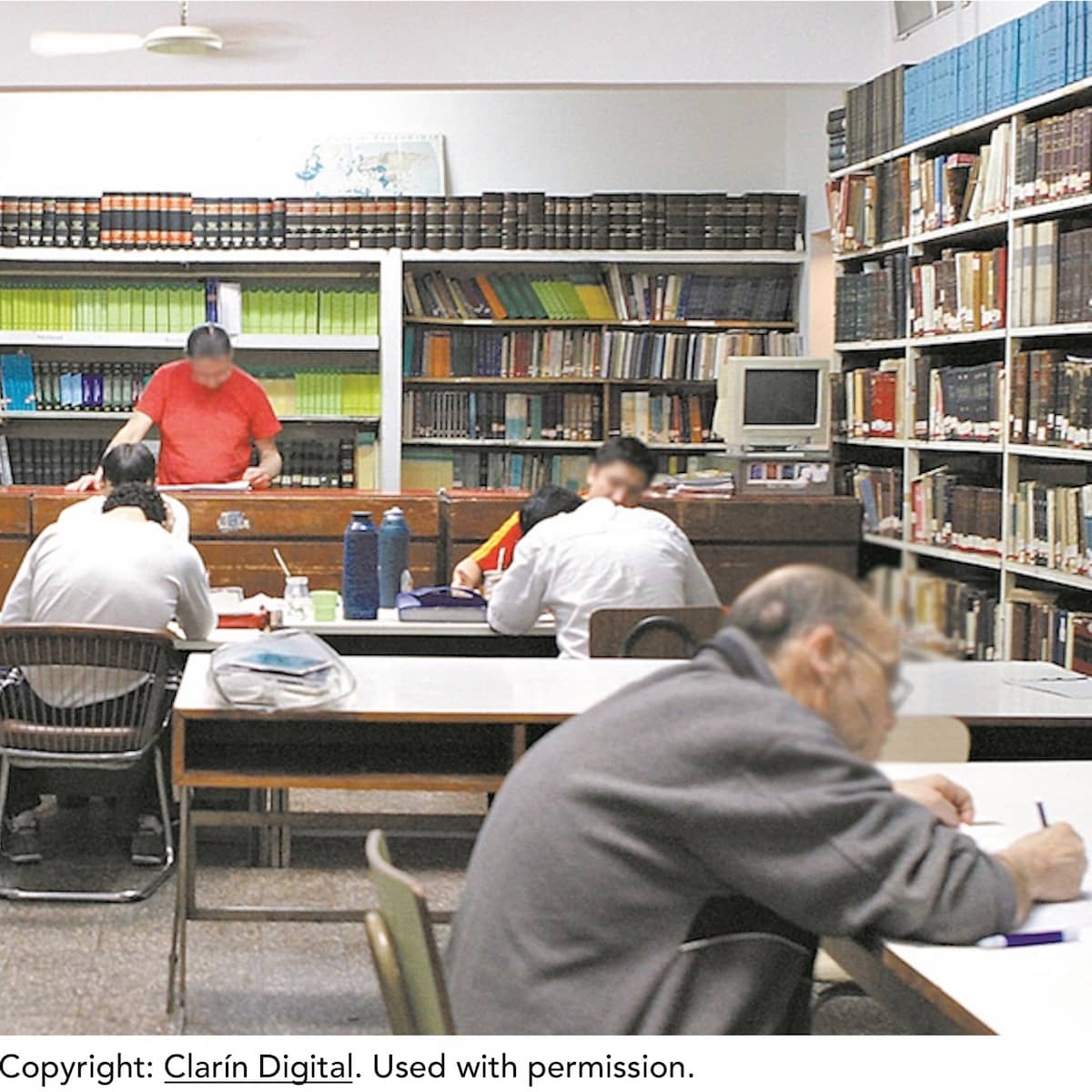

One day, Martin signed up for a literature class in prison. Eventually he began reading short stories in his free time between scheduled meals and shower times. “Martin, as well as my other students, were really into El que vino de la lluvia by Hector Tizon,” says Juan López. For several years, Juan taught Language and Literature in prisons in Mendoza, Argentina.

This crime narrative tells the story of a retired judge (Álvarez) and El Rana, a Chilean whom that judge had erroneously accused of a homicide fifteen years earlier. It exposes how precarious the law is, and how the police sometimes act with few clues or even a lack of evidence and witnesses.

It was simple enough for students with different reading abilities to understand it. However, it was also rich enough to provide them with food for thought.

Experience Shows Power of Education for Inmates

The classroom is an important space in spite of penitentiary limitations. Prisoners can develop valuable skills and relationships with their peers and teachers regardless of which prison we are talking about. This phenomenon is particularly important in countries with punitive-based prisons like Argentina and the US. Simply put, the classroom provides freedom that cells lack.

Teaching Has Greater Impact for Prisoners than Free Citizens

Juan, who taught in high schools before teaching in prison, explains how his profession seemed more valuable in prison. “Many of my students learned how to read and write in prison despite being adults, something I had not experienced before as a high school teacher.” Prisoner education is different from typical school education, partially because the population presents higher illiteracy rates than free citizens[1].

Teaching was Juan’s way to help prisoners not suffer ‘double’ punishment. “The only thing prisoners are deprived of is their liberty, not any other right,” he says.

The prisoners are different from regular students, who have relative freedom during non-school hours, immersed in a disciplinary environment 24/7. “You would go to school, and then leave, but my students just went back to their cells,” Juan explains.

Is Prison Only for Punishment, or To Ensure Successful Reintegration to Society?

Prison life is a punishment. Prisoners are deprived of their most individual liberties. They lack any sense of personal space, and they are barely permitted to see their families. This makes prisoner education particularly important. It equips them with skills they can apply upon release, and provides them with a sense of purpose in their daily lives. Education provides higher social stability, improved health and livelihoods, and long-term economic growth.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) supports the right to education for all prisoners. Resources are supposed to be offered in prison in order to help inmates reintegrate back into society. With that, education becomes even more important in a controlled and artificial setting.

Education Is Humanizing for Inmates

Besides long-term benefits and a sense of purpose, educational settings also allow for emotional support. Juan’s students wrote about not seeing their families as frequently as they wished, being mistreated by some of the guards, or being tired of eating the same food on a regular basis. Besides being a place where they could voice their struggles, the classroom also gave inmates a safe space to voice their curiosities.

Students often asked for a history or philosophy book, or insisted on learning Braille because one of their peers was blind. One student, Pedro, kept Juan updated on the cheese he made from cafeteria milk and explained the entire process to him. The classroom was a mentally liberating and humanizing space that allowed prisoners to be humans with creative skills and intellectual potential, rather than simply ‘evil’ inmates.

Teachers Provide a Connection to the Outside World

Incarcerated students see their teachers as a means to keep in touch with the “outside world.” The students did not want Juan to be someone “morbidly interested in the violent aspects of prison life”. They wanted someone who would give them an insight into what is going on outside of their prison conditions.

Prison regulations frequently forced Juan to reject requests for magazines or newspapers, but he was able to discuss current events with prisoners privately during breaks. Communicating with their teacher beyond the curriculum was one way to stay in touch with outside society, and take a mental break from physical confinement and life in prison wards.

Unique Challenges to Education While Incarcerated

Rough living conditions create some extraordinary challenges for class attendance. “Unless you’ve been in prison, you can’t know what it is like to live there”, Juan says.

In a regular school setting, students would miss class if they were sick or had a medical appointment. But in prison, classes were often suspended due to security issues or students missed class to attend their preliminary hearings.

These tough circumstances make participating in prisoner education quite an impressive achievement that requires discipline and perseverance. And, it also explains why less than 50% of Argentine or American prisoners take classes.

Education Encourages Accountability

Prison education also functions as a system of accountability.

Incarcerated individuals respect their teachers partially because of how conduct impacts prisoners’ ability to attend class. Students tried to make a good impression on Juan because they were aware of the consequences of misbehaving.

What caught Juan’s attention during his time teaching in prison? “Sometimes students would ask me to tell correctional staff that their behavior has improved (…) they knew that studying was a good sign”. Regular students perceived their teacher as someone who can hold them accountable for their actions.

Going to class has a cascading effect that surpasses what prisoners learn during class. They are not only learning content that will help them develop life skills but also growing awareness of how misbehaving or exercising violence would affect their chances of attending class.

A study on Argentinian prisons done by researchers from the Pontifical Javierian University shows how education lowers the probability of in-prison conflict. Even from a logical standpoint, more time spent studying means less time available to engage in conflicts. Education is thus also an overall promoter of good, non-violent behavior.

Benefits of Prisoner Education Continue After Release

Prison education programs also carry benefits that go beyond individuals’ time in prison.

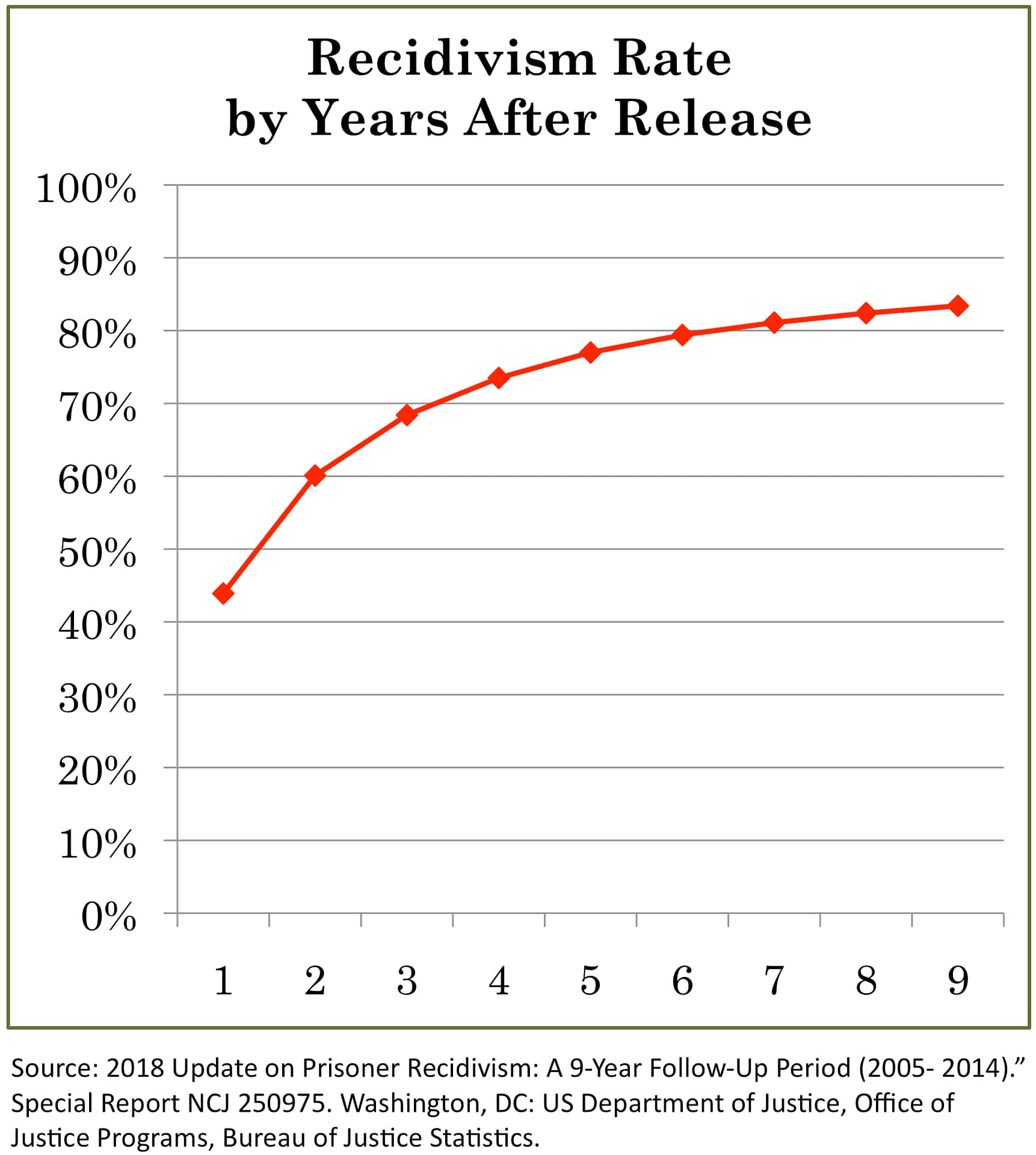

Studies around the world show that education not only reduces in-prison conflict but also lowers recidivism rates. This is also of particular relevance in the US as one of the countries with the highest recidivism rate where 76.6% of prisoners are rearrested within five years2. A study by the RAND Corporation found that participation in prison education programs reduces recidivism by 43%.

Prison education has helped many incarcerated people reform and become gainfully employed, preventing them from going back to criminal behavior. In Argentina, around 85% of prisoners who attended educational programs do not backslide. Once prison education equips prisoners with the tools they need to reintegrate into society and find a job, they are less likely to re-offend.

Prisoner Education Programs In America Don’t Get Sufficient Attention or Respect

In spite of available evidence of the positive effects of prison education, correctional education in the US continues to have many problems. These include:

- Staff shortages

- Lack of funding

- Inadequate space

- Poor planning

- Low status due to the assumed (punitive) role that prisons play in American society

Unless there is a structural change in America’s approach from prison as a place only for punishment to one for rehabilitation, educational improvements seem unlikely.

Is There a Happy Ending?

A couple of years ago, and fifteen years after Juan stopped teaching, his taxi driver happened to be Martin. “Profe?” (teacher?), he asked. Juan, who did not recognize him at first, could not believe it. They talked and caught up during the rest of the trip. It was the first time Juan had seen a student outside of prison.

Juan is moved every time he hears from one of his students who got a job after being released. This anecdote not only expresses the pride that comes with experiencing this first-hand but also proves the social responsibility and radical impact that prison educators have on prisoners’ lives; both during and after incarceration.

Why Does America Resist Seeing the Benefits of Prisoner Education Programs?

Some Americans insist that educating prisoners is costly. Tax dollars down the drain. However, the same study by the RAND Corporation, quoted by President Barack Obama in support of the Second Pell Grant, which offers need-based aid to incarcerated individuals to participate in post-secondary education programs, shows that education not only lowers recidivism rates but that $1 spent on prison education saves $4 to $5 on incarceration costs. Taking into account how costly it is to maintain prisons provides more evidence of the cost-effectiveness of prison education.

Some people argue that not everyone can be rehabilitated, that not every prisoner can participate in education. Some prisoners suffer from serious mental health issues that can prevent them from improving and lack the support that is required to change or study. However, under curable conditions and psychological support, this is the exception to the rule.

On top of that, not all prisons are the same. Some prisons have better educational programs than others due to factors like proper infrastructure or staff availability.

The work of criminal justice non-profits is particularly important to overcome these inequalities. Prison Scholar Fund, Ameelio, Prisons Foundation, Human Kindness Foundation, Whole Soul are some of the organizations that understand education as an equalizer and have embarked on the mission to improve prisoners’ conditions and opportunities. Since changes in correctional education policy are long and complicated processes, supporting organizations that have a positive impact is key.

Conclusion

Prison classes are one of the few ways Argentine prisoners can improve their lot and express their humanity. As Juan puts it: “Teaching in prison taught me that there’s not a huge difference between someone who committed a crime and you or me”.

Going from a punitive to a rehabilitative system requires an understanding of prisoners as people with human rights and potential and not as stereotypical criminals. Prisons should not be simply negative spaces of social control and reclusion. Prisoner education matters.

Related Articles

- Prison Education Programs: What To Know

- The Societal Benefits of Post Secondary Prison Education

- Education Opportunities In Prison Are Key To Reducing Crime

- Prison Education In America: The History and The Promise

- Prisoner Reintegration: Lessons From Norway

Footnotes

[1] According to the National Adult Literacy Survey, 70% of all incarcerated adults cannot read at a fourth-grade level, “meaning they lack the reading skills to navigate many everyday tasks or hold down anything but lower (paying) jobs.” ⤴

[2] Source: 2018 Update on Prisoner Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-Up Period (2005- 2014).” Special Report NCJ 250975. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/18upr9yfup0514.pdf ⤴