Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Impacts Basic Services and Living Conditions for Inmates

In this article, we shine a spotlight on how decades of fiscal mismanagement by Puerto Rico’s government, and a pair of devastating natural disasters in Hurricanes Irma and Maria have pushed the island’s prison system to the brink of collapse.

Seven years later, and largely forgotten on the mainland, the ensuing debt crisis continues to impact living conditions for inmates, any kind of prison reforms, and has even compromised basic services such as the food supply chain.

It Got So Bad, Shipping Inmates to Private US Prisons Seemed Like a Good Idea

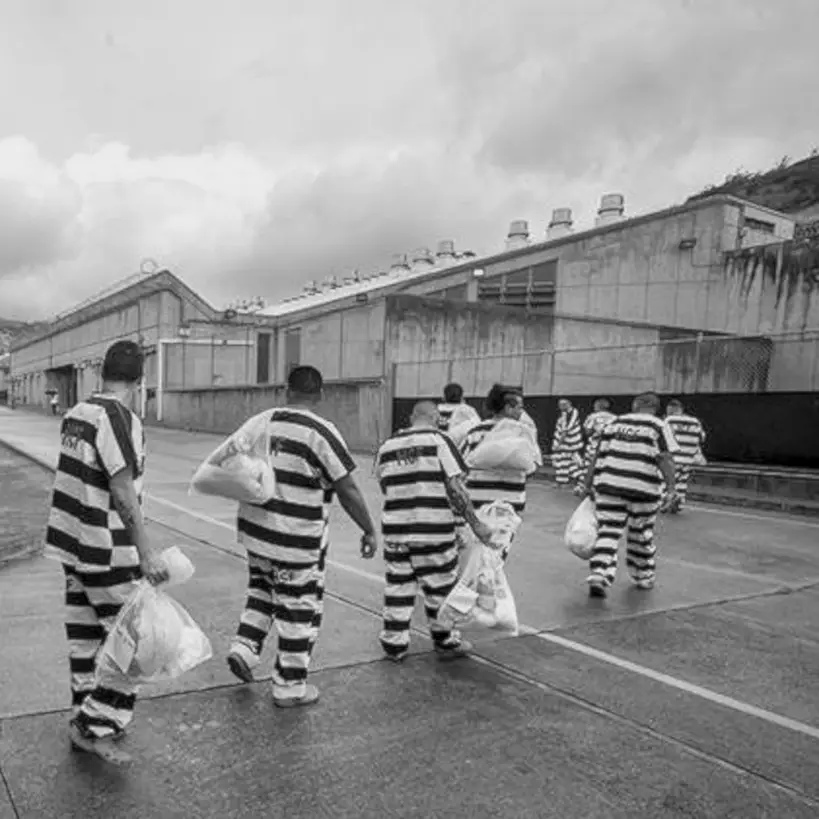

In 2018, a media outburst exploded around Puerto Rico and the government’s decision to move 3,200 inmates, from its prison system to private prisons within the United States.

Already embroiled in a debt crisis that had been growing since the early 2000s, Puerto Rico made this decision in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, as part of a series of austerity measures. The government described the transfer program as completely voluntary, but had already begun contract negotiations with CoreCivic, a private corrections company, for potential incarceration facilities.

Joseph Villalobos, an inmate at Bayamon Maximum Security Annex 292, represented the vast majority of inmates and their families in his skepticism. Commenting to The Guardian, he doubted the voluntary program would remain voluntary. “Once you’re in jail and you’ve got that sentence on you, they dictate the rules”.

Beatriz González, the partner of inmate Carlos Luis Colón Santos, expressed similar fears to the Puerto Rican Cultural Center that isolating inmates from their support networks would create feelings of anxiety that lead inmates to lose the progress they have previously made.

Two years after the federal government established a fiscal oversight board to address Puerto Rico’s debt and less than half a year after Hurricane Maria devastated the island, the externalization of public services appeared to be a timely and necessary solution.

This program has since been quietly canceled.

Why?

A Desperate Response to Prison Overcrowding and Lack of Money

Puerto Rico’s Department of Corrections head says the plan was needed to address immediate overcrowding after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. He insists that once overcrowding was resolved and disaster relief began progressing, rehabitation was no longer required.

Yet five years after this plan’s public castigation, there appears to be little resolution for the fiscal goals and austerity measures that had been the initial justification for the government’s announcement.

Puerto Rico Economics From World War II to 2015

Puerto Rico is distinctive among US territories due to its treatment by all US departments and officials “as if it were a state” due to their right to internal self-government through its local constitution.

In the post-World War II period, Puerto Rico passed the tax-incentive law Section 936 in 1976 in order to attract greater economic investment and industrial growth. While the bill succeeded in attracting hundreds of corporations to the island, there was little effort by corporations to expand business operations and increase the number of jobs offered.

When Congress began phasing out this tax break incentive in 1996, the territorial government began borrowing money rather than cutting down on spending. But this excessive spending and borrowing severely weakened Puerto Rico’s capacity to withstand any kind of systemic shock.

By the time that Section 936 was phased out in 2005, Puerto Rico was deeply in debt, and the global financial crisis of 2008 delivered a hard gut punch. The economy no longer possessed the development or stability necessary to stand unaided.

The decades of economic decline and government borrowing after 1996 had compounded into the then governor’s announcement that “the debt is not payable” in late June of 2015. As a US territory, Puerto Rico was unable to receive assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) like a country, but also unable to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection like a US municipality.

Debt Crisis Becomes Humanitarian Crisis

At this pivotal point, the island’s debt crisis had already erupted into a humanitarian crisis, with massive budget cuts leading to public service workers remaining unpaid for months at a time. This crisis bled into every aspect of government services, including Puerto Rico’s prison system.

After owing more than $12 million in debt to the prison system’s food vendor, the vendor decided to stop sending supplies to all 37 operating facilities holding almost 12,500 inmates, an act which threatened to interrupt the food supply chain completely.

Mismanagement of Available Resources Compounds Problem for Puerto Rico’s Prisons

A study by George Mason University found that the Department of Corrections (DOC) was maintaining facilities with underutilized adult and juvenile facility spaces with uncommonly low officer to inmate ratios. This mismanagement of resources combined with a refusal to privatize or subcontract prison operations to private firms all led to criticisms that it was neither efficient nor reasonable for the DOC to account for almost 5% of the general fund’s 2015 budget.

The inefficiency of the administration was clear, and the pressure to reduce the budget for public services felt all the more urgent.

PROMESA Creates Fiscal Control Board, Squeezes Island to Pay Debts

In response to what was the largest bankruptcy crisis in the U.S, Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) in June of 2016.

This act appointed a fiscal control board of seven members to oversee the island’s finances and restructure the territory’s debt. In reaction to a debt crisis, this board was imbued with the power to rebalance the government’s budget and to restructure all $65 billion of the island’s debt with all bondholders and creditors.

In his book, Prexit: Forging Puerto Rico’s Path to Sovereignty, Javier Hernández describes the unfortunate message sent by the passing of PROMESA, that “The U.S. Congress is obligating Puerto Rico to pay for its own colonial humiliation and the failures of U.S. colonial rule.”

Puerto Rican anxiety about PROMESA went beyond nationalistic sentiment. The fiscal control board’s primary mandate and responsibility was debt repayment above all else. La Junta, the colloquial name given to the oversight board, was empowered to restructure the island’s debt. But, they held much less power in pressuring creditors to accept restructuring offers.

In committing itself to repaying Puerto Rico’s debt by all means, the board had effectively made the choice to use its near absolute control over financial policy to push for austerity measures and to meet short-term needs to appease its bondholders.

Then Came Back-to-Back Hurricanes, Devastating Infrastructure

On September 7, 2017, Hurricane Irma passed just 30 miles off the coast of Puerto Rico. Just two weeks later, on September 20, Hurricane Maria made landfall on the island.

The two hurricanes absolutely devastated the island and its people, with high wind speeds and storm surges. The back-to-back natural disasters forced Puerto Rico to officially declare bankruptcy just a year after La Junta’s creation to prevent this very declaration.

The disaster forced La Junta to restart all fiscal plans and projections they had created in 2017. The island’s GDP had dropped by 11%, and its population had dropped by almost 8% due to Puerto Ricans moving away in search of more job opportunities in the mainland.

A research study showed that Washington’s allocation of disaster aid only arrived at the island four months after the hurricanes. At this time, Governor Ricardo Rosselló had submitted a request for $35 billion in federal disaster relief aid for long-term recovery and infrastructure construction assistance.

After the four months, when FEMA disaster relief totaling only $4.9 billion in loans were finally dispersed to Puerto Rico, these funds were further entangled in a separate dispute which extended the time for recovery measures.

La Junta Calls for ‘Externalization’ to Reduce Costs

During this fiscal crisis, La Junta had drawn a newly proposed plan which counted upon FEMA disaster relief funds to bolster the recovery of the island, and called for the privatization of electricity to lower the costs of restoring the electrical system. The fiscal plan of 2018 repeated “consolidation” and “optimization” over and over within each agency and department.

Nestled amongst pages and pages of austerity measures was a singular line that would set off a firestorm of indignation: “Reduce per diem cost through externalization of services to approximately 3,200 inmates (30% of imprisoned population).” A tidy bar graph projected that the Department of Corrections would cut $395 million by 2023.

Beyond the neat numbers and reasonings provided to justify the rehabilitation of inmates, an outpour of indignation on behalf of the prisoners ensued. Criminal justice advocates and the representatives of prison inmates called out their moral concerns, decrying this attempt to tear apart families and to move people against their will.

CoreCivic, the private prison company partnering with the Puerto Rican government, held recruiting events for bilingual officers. Unfortunately, private companies and mainland facilities lacked understanding of Puerto Rican prison culture and were poorly equipped to deal with possible disputes.

Backpedaling on Externalization Plans

Months later, the territorial government had yet to finalize inmate transfers, and pushed back upon signing a contract with CoreCivic. The ambitious plan was quietly shelved, just as quietly as it was originally announced.

In September of 2019, La Junta had achieved notable success with debt restructuring: announcing a plan which would reduce $129.2 billion to $86.0 billion in public debt obligations. A federal judge approved additional reductions in debt obligations, finalizing the plan in January of 2022.

Nevertheless, the tightrope balance between managing a fiscal debt crisis and maintaining basic public services is a problem which bleeds into each government agency and department, whether or not there is a disaster to exacerbate the circumstantial difficulties. Puerto Rico’s annual economic growth still hasn’t been able to achieve consistency, with significant drops in GDP and population shrinkage between 2004 to 2021.

In the 2023 certified fiscal year plan by the Fiscal Oversight Board, the Department of Corrections and any overt mentions to the carceral system are missing from all three volumes.

The government lacks choices. Without money, prioritizing reforms and resources for the general population versus the incarcerated population is nearly impossible.

Austerity Means Lots of Plans, But Little Progress

This theme extends into the Plan Estratégico 2021-2025 laid out for the Puerto Rico Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. With comprehensive programs laid out for 6 assistant secretaries and various regional offices under the head Secretary of the DOC, there is a sense of push and pull between modernization and efficiency as well as the need to conform to austerity measures and budget confinements.

Under the Assistant Secretary for Programs and Services, one of the plans seeks to establish a community outreach program for the juvenile population to reduce recidivism. Another plan seeks to increase access to vocational studies and work preparation.

Other branches under the DOC also seek to develop programs for improving accessibility to legal manuals and creating better living conditions. The regional offices under the DOC have plans to improve water storage capacity at Ponce Correctional Complex, to demolish correctional facilities affected by earthquakes in the southern region, and to find safe and suitable sleeping areas for employees during major emergencies.

Especially within the regional offices, these plans paint the picture of local facilities that are struggling to maintain basic infrastructural systems while also attempting to push for reform.

Yet, the strategic plan specifies a need for greater funds in many places for program implementation. However, the Assistant Secretary of Management and Administration was also asked to consolidate facilities, and conduct a comprehensive study of which investments for correctional institutions could be considered unnecessary and counterproductive.

Some measures of this plan have taken place already, with the closure of 10 prison buildings as well as other facilities integral to university research studies for confined people.

Little Improvement in Inmate Living Conditions; Rehabilitation, Reintegration to Society Suffer

Amidst these changes, there remains a consistent inability to fully improve the living conditions of inmates in existing facilities and to assist their rehabilitation and the process of reintegration.

In an exchange with Linda Backiel, the president of the Puerto Rico Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, she compared the Metropolitan Detention Center in Guaynabo –a holding facility subject to federal standards– to local prisons in Puerto Rico –subject to jurisdictional direction. She describes how “MDC has air-conditioning, [and] provides basic personal care supplies.

[While] Medical care is still inadequate, but some in-house attention [is] available, in theory, at least every weekday (often PA or nurse).” Backiel states “Minimal standards of cleanliness are generally met [in MDC],” but this was “not always the case in state institutions.”

Balancing requests for improvements from within the prison system with a debt crisis creates unrelenting pressure from outside the system. Criminal justice reform will only be considered in Puerto Rico after it sticks a price tag on itself.

Endgame: Puerto Rico’s Austerity Measures Trump Humanitarian Obligations and Social Needs

The overlap of a humanitarian crisis upon a fiscal crisis means that there should be a humanitarian obligation to view each success through the lens of human cost.

PROMESA and the Financial Oversight and Management Board assumed that having a smaller body of officials would be more efficient in resolving a financial crisis than the democratic process. But, these “tough” decisions and bright successes ultimately deprioritize social needs.

This struggle between advances and concessions is best framed by Backiel’s description of the opportunities established within the PR prison system: “PR prisons do have programs, some very good, leading to college degrees, agricultural and entrepreneurial skills, too little for too few, but something.”