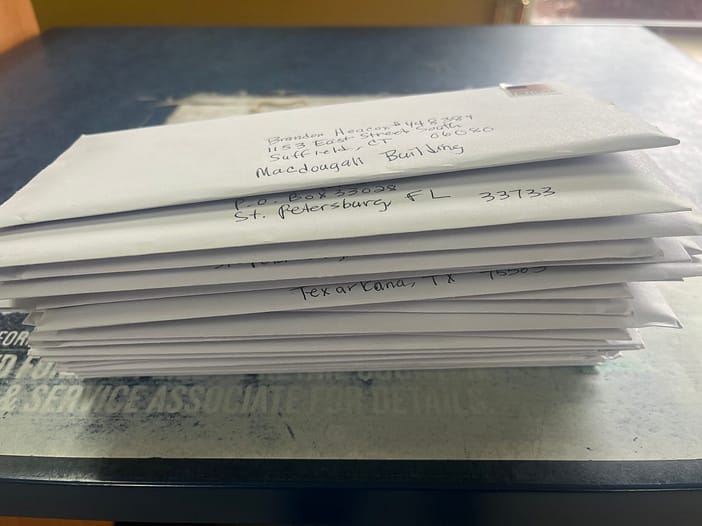

Each month, Impartial receives on average between 30-40 letters inquiring about our Prison Artwork program. These letters come from individuals across the US prison system, each with unique stories and needs.

I respond to every letter. To do so effectively, I’ve developed a system that allows me to dedicate focused time, usually over the weekend, to read and respond thoughtfully. It’s not just about providing program information—it’s about understanding and addressing the humanity behind each letter. With a stack of envelopes, stamps, forms, and blank sheets of paper, I prepare myself for the range of emotions and requests that await me.

Some letters are straightforward, containing a simple request for information about the artwork program. Others, however, are much more personal. I’ve received one-sentence notes, 8-page life stories, and everything in between. The handwriting varies from breathtaking calligraphy to childlike scrawls written in crayon. Some letters arrive typed on typewriters, others scribbled on the back of the correctional facility’s commissary order forms. Each piece reflects the sender’s circumstances, creativity, and determination.

Many of these letters carry an unspoken plea for help, woven through their words. While I wish I could do more, my role is to support them through their art.

Returned letters are a reality I’ve had to accept. My stack of returned mail—or rather, the plastic bag holding letters marked “undeliverable”—is a reminder of the system’s complexities. Letters are returned when prisoners move facilities, are released, or if the envelope doesn’t strictly follow the format. Keeping up with the particulars for each prisoner at each facility is something I have had to learn to do. For instance in some states, I must use my full name in the return address rather than just my initial. In other states, letters must be addressed to a processing center that then scans and sends them digitally to the intended recipient. While this process ensures safety, it’s disheartening for loved ones whose carefully scented, decorated cards or handwritten notes are never received in their original form.

Some prisoners ask me, “What should I draw that people will like?” I often respond, “Chances are, whatever you love to draw is what you draw best, and others will appreciate it.” It’s a heartfelt answer, though I know it’s not always what they hope to hear. They seek validation for their work, but without knowing their skill level or creative vision, it’s difficult to provide more specific guidance. Still, I strive to answer with compassion and realism.

For many, art is a lifeline. It’s a way to express themselves, connect with others, and find a sense of purpose in challenging circumstances. Prisons can be tight-knit communities, and aspiring artists often find or create support networks within their facilities. One artist I’ve corresponded with for years shared how a group of prisoners collaborates, teaching each other techniques and waiting for humid days to practice blending methods—a resourceful and inspiring insight.

These stories remind me why this work matters. Through art, prisoners share pieces of their world, their struggles, and their resilience. My role is to encourage and support their creativity, helping them find a voice and purpose through their artwork. I will continue to write back, fostering understanding and appreciation for their efforts, one letter at a time. The final touch of irony in this process is placing the “freedom” stamp on the prisoner letter.