Latin Roots

The word justice is derived from the Latin words jungere (to bind, to tie together) and jus (a bond or tie), reflective of a conjoined notion that functions as a tool to organize people into groups and distribute each person his or her due share of rights and duties, rewards and punishments. The Roman Emperor, Justinian, explicated upon the fundamental elements of justice that are based on Aristotle’s theory of “treating of equals equally and unequals unequally in proportion to their inequalities.” Additionally, he had identified three specific types of justice: distributive justice, corrective justice, and commutative justice. So how does this translate in a contemporary context? It’s a staple of sound judgment that we don’t allow judges to try their own cases. The virtue of justice ideally mandates not only that we judge others fairly, but also that we judge ourselves fairly. Thus, justice begins within ourselves. While justice is relatively applicable and significant for each of us in our own lives, it becomes remarkably quintessential when we think of those wielding positions of authority. Leaders implored by a zeal for justice and not merely self-aggrandizement is an exigency, not a luxury. It is inexplicably inescapable that the end result of leadership without an internal moral compass accurately guiding towards justice is an abuse of power.

The definition of justice typically manifests into a host of shapes and forms with situational attitudes of those who are affected by crimes or acts of grievance. Being the victim of a crime alters the way you perceive justice. Justice becomes highly personal. It is believed that justice is the first virtue of social institutions due to its affiliation with life and cosmic plans such as fate, reincarnation, and divine providence. In 2008, the University of California, Los Angeles conducted a study that demonstrated that reactions to fairness are “wired” into the brain. Hence, “fairness is activating the same part of the brain that responds to food in rats…This is consistent with the notion that being treated fairly satisfied a basic need.” On the same note, Emory University piloted a study in 2003 that used Capuchin Monkeys to shed light on the fact that “equity aversion may not be uniquely human” which is indicative that the principles of fairness and justice tend to be inherent by nature.

Social Justice

Unlike justice in a comprehensive sense, social justice is a rather recent phenomenon. Its inception is credited to the struggles concerning the industrial revolution and the creation of socialist perspectives on the organizational nature of our societies. Justice is the premise of fairness; social justice is fairness as it materializes in society. Social justice endeavors to bequeath each member of society, despite rate, ethnicity, gender, income, etc., the same opportunities and protections as everyone else. Criminal justice is a subset of social justice. The poorest and most vulnerable are disproportionately more susceptible to being wrapped up in our criminal justice system. Racial barriers that hinder fair treatment and responses in policing, sentencing, incarceration, and reentry into society are calculated, systemic, and structural.

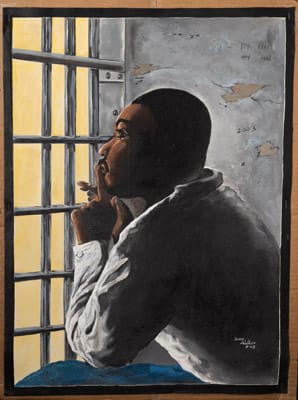

Racial Implications

Since the Reconstruction era, ethnic and racial minorities have constituted a disproportionate share of the United States prison population, leading the globe incarceration rates. Racial disparities within the criminal legal system are deeply rooted and extensive. President Nixon’s policies stemming from the declaration of the War on Drugs in 1971 in conjunction with “tough on crime” rhetoric resulted in an uptick in the United States prison and jail populations. A report published by the Council on Criminal Justice analyzed disparities in state prison rates and in 2016, the ratio of Blacks to whites was five to one. However, the number of Black offenders for crimes such as robbery, assault, rape decreased 30% since 2000. Black individuals are still being locked up for drug times at five times the rate of white people and are expected to serve more time regardless of the crime being violent or drug related. John Enrlichman, President Nixon’s Policy Chief, was expounding upon Nixon’s War on Drugs and was quoted saying “You know what this was really all about? The Nixon Campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people…We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them right after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

The United States faces the brunt of yet another iteration of calls for social and racial justice following multiple deaths of Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement. It is time to engender and institute formidable structural reforms that will augment fairness and safeguard proportionate punishment without sacrificing public safety. Despite the fact that America has the highest incarceration rate in the world, individuals spend months in jail awaiting trial and those convicted are more likely than any other nation to receive long carceral sentences. Against this setting of reinvigorated calls for racial and social justice in retortion to deaths of Black people at the hands of law enforcement agencies, the coronavirus pandemic has shed light on America’s abominable jails and prisons, where those pending trial or serving sentences have been subject to disproportionate rates of infection and death due to the rapid spread of the virus in the close quarters. Since the first modern-day legal system commenced in Rome, the scales of justice are exploited to represent the balance between the truth and fairness. Those involved in the political decision making process must keep such ideals in mind.